Antony Green, Australia’s best-known psephologist, has retired from his public role at the ABC but is fortunately still blogging from time to time. Two recent posts deserve some attention.

The first, at the beginning of last week, looked at the results of the 2016 reform to Senate voting, which abolished group voting tickets (GVTs) – a reform that Green, like me and most other psephologists, strongly supported. He explains the change and presents figures to show that the average number of Senate candidates has declined steadily since then, and that the vast majority of voters simply number groups from one to six above the line, the minimum number that the instructions tell them to (although in fact a failure to number as far as six will not render the vote informal).

He also gives a breakdown by party of how people vote in the Senate (whether above or below the line, and how many groups they number), showing that those who vote for minor parties are much more likely than major-party voters to vote below the line, where they can number individual candidates.

I found this fascinating, because three years ago I looked at this question for the Victorian state election, where voting was (and is) still by means of GVTs. Voting above the line there meant adopting a party’s preference ticket, and I suggested that the uninitiated might therefore expect “that there would be less above-the-line voting in the case of parties that appeal to self-styled individualists.”

In fact, as I pointed out, the figures showed the opposite: at the 2018 state election, the Liberal Democrats (now called the Libertarian Party) had the highest rate of above-the-line voting among minor parties, while the parties with the lowest rates were on the left.

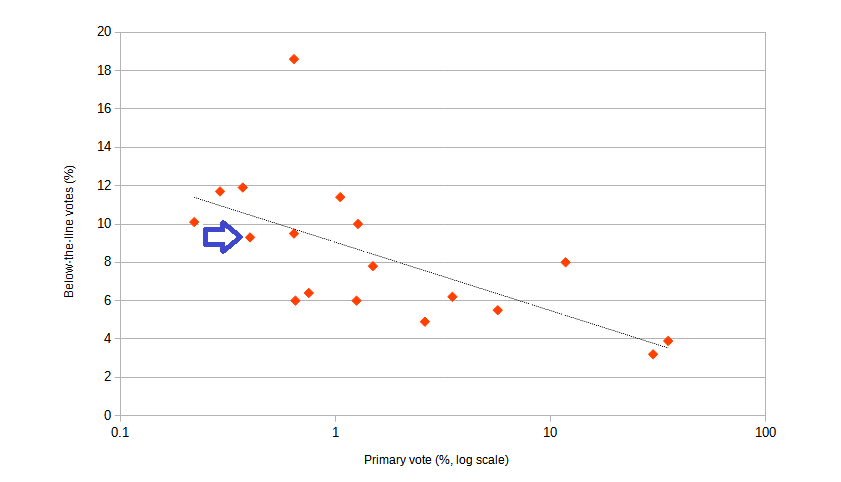

What’s interesting about Green’s analysis is that federally, with no GVTs, that ideological correlation mostly disappears. I made a graph showing the relationship between a party’s share of vote and the proportion of its vote that’s below the line; the trend is clear, and the Libertarians (marked with the arrow) are only just below the trend line. (The one serious outlier is the Trotskyists, up the top with more than 18% below-the-line.)

The second post of interest was just a few days later, and it’s about strategic voting. It’s long been a truism of Australian politics that the major party vote is higher in the House of Representatives than in the Senate, and vice versa for minor parties. In this year’s federal election, however, Labor’s vote was actually higher in the Senate than in the House: 35.1% to 34.6%.

What Green shows is that the difference is attributable to a small number of seats in which Labor’s vote in the House was very low and the actual contest was Coalition versus independent (generally Teal). Clearly, people who are normally Labor voters were voting Teal, and since there were no Teal Senate candidates* they reverted to voting Labor in the Senate. If you take out those seats, the relationship looks the same as usual.

It’s not surprising to find this sort of strategic voting (there was already some discussion of it after the 2022 election), but it’s good to have it confirmed and Green’s discussion is very informative. Don’t miss the comments, and especially the first one in which he’s confronted with the argument that the strategic voting was misguided because if Labor had got ahead of the Teals it would have won on their preferences. Green isn’t convinced (for what it’s worth, neither am I), but whether you agree or not his response is a model of careful reasoning.

I doubt that there’s anything special about Labor voters in this regard. There weren’t many seats in which Liberal voters were given this opportunity, with an independent potentially able to beat Labor, but as Green points out in two where they were, Calwell and Fowler, they showed the same split between House and Senate voting. Clearly the independents aren’t going away any time soon, so the opportunities for strategic voting on both sides may well multiply. And as Ben Raue argued in 2023, the fact that so many voters now have to grapple with these questions makes our electoral system less fit for purpose than ever.

.

* Except in the ACT, where, sure enough, the Labor Senate vote was much lower than its House vote – hugely so in Canberra and Fenner, less so in Bean, where there was also a Teal running for the House. Note also that, counterintuitively, “strategic voting” and “tactical voting” mean the same thing.